Today I am thinking about genius, what it really is, how we may recognize it in others, and whether it is essential to work as a scientist.

My biology professors, over the years, have expressed repeatedly that biologists don't need to be geniuses to be good at their jobs, just smart, persistent, and able to write well enough to publish. From what I can tell, these men are geniuses, so I could either believe these genius professors or I could suppose that they are just wrong, being too humble or too ignorant of their own intellects to judge correctly. They seem pretty honest, so I am going to reject the other possibility that they are just lying to non-genius me to encourage me in a pointless effort at a scientific career.

Biologists enjoy wallowing in humility, I think. We are the commoners of science, with our dirt and our blood and our need for experimentation, and we relish this proletarian role. We are, alas, also prone to emulating dirty hippies. Science itself is an ego-buster. Trying the same experiment, over and over, only to have it fail repeatedly due to impure chemicals, electrical failures, old equipment, grad student foolishness, or biological impossibility starts to feel like you are bashing a brick wall in with your head. Problem-solving is so much fun, but the really great problems require a high level of pain tolerance. Or masochism. Whatever. Even the tiny problems have hidden difficulties. I told my parents once that my thesis is 20 steps long, and I was stuck fiddling with step 3 for 5 months.

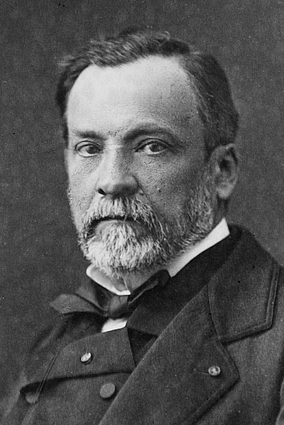

Anyone who works in any field of science knows this struggle and how hard it is, and so may discount the role of genius. What is genius? Is it simply extremely high intelligence? In the popular imagination, I think it is more. We have the figures of genius in our mind's eye when we speak of science or art or music. They were more than just smart men or prodigies, but had something special, some profound and world-changing insight that put them high above all the rest. Pasteur, pictured above, is one of my favorite scientists because of his varied and important contributions to chemistry and microbiology. I visited the Pasteur Institute and was amazed, seeing the displays of all of his microbiological experiments together, that this had all been the work of one man. He had also painted the skilled Pasteur family portraits hanging in his house. Amazing. I also learned that the French do an impressive job honoring their dead scientists. Alternatively, one could say that anyone in the top 1% IQ of a population (or 0.1% or 0.01% if the test can actually tell those apart) counts as a genius, and that's who scientists should be. Mensa takes the top 2%. If that's all you need, maybe everyone in science is a genius. I don't know because I don't think they know their scores.

How can we recognize genius in other people? I am not all that interested in getting into the IQ testing arguments, so let's say that the IQ test actually can identify geniuses. Even if it can, few adults actually know their IQ. The Facebook test designed by a 6th grader doesn't count and actual IQ testing costs money. Standardized tests like the SAT or GRE might tell you something, but I have to say the math portion of the GRE is kind of a joke -- high school algebra and geometry. No trig, no calculus -- that would require a calculator. So easy it hurt. I do feel sorry for the humanities majors who thought they had seen the last of those problems 4 years prior and had to try to relearn the formula for a cylinder's volume. That test won't find a math genius because the math problems are too easy.

Something else is needed, and that's where the resume or CV comes in. Lots of publications that are cited many times indicates the ability to deliver exactly what a university wants from its faculty: lots of publications that are cited many times. They don't care if a prof is a genius, as long as he is prolific. Producing results and being able to communicate those results are two different things. Genius might help with either, but biology is such a plodding sort of field most of the time that I think you probably don't need much more than high intelligence to succeed -- the same high intelligence required in law or business, but with a different kind of analytical focus.

Good communications skills are a different thing than experimental design or scientific insight, and they are so important that they can actually compensate for relatively poor scientific abilities. Writing a clear paper means people will actually read it closely enough to cite it. I have heard, repeatedly and to my chagrin, that the most important for success in academic science is writing frequently and well.

DRAT!!!

If genius were the main requirement, I could always hold out hope that I Sekritly Am One and everyone else is just too mundane to see it or too jealous to acknowledge it.

Wow! Sciencegirl has a blog! Sciencegirl has a blog! I am intrigued.

ReplyDeleteMy theory is this (and as somewhere between biology and agriculture, I am sooo far more a commoner of science, that probably quite a lot of scientists would ponder denying me that title):

It takes

1) Genius,

2) Very Hard Work,

3) Ruthlessness and Scheming, and

4) Luck,

in varying proporions, to be succesful in my field.

Having arrived at this theory - I thoroughly put my trust in Luck...

Notburga